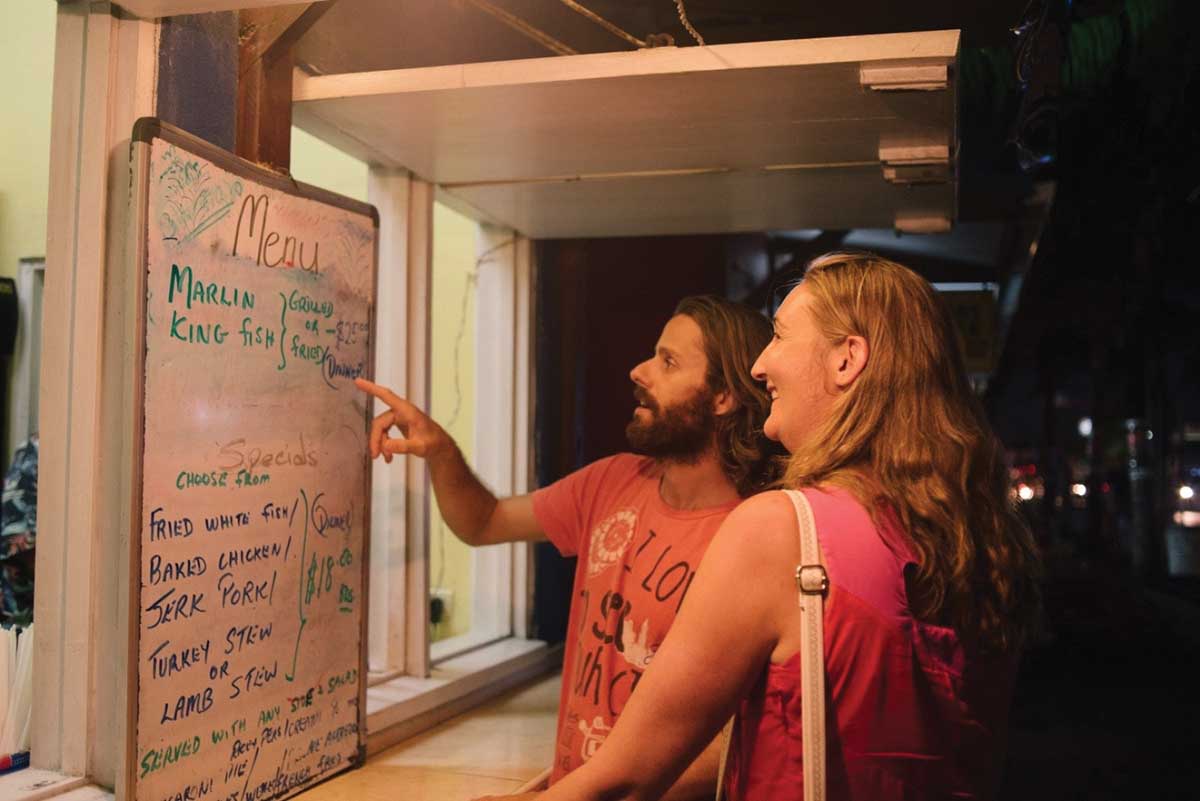

Few activities are more Bajan than a Friday night visit to Oistins fish fry. Cooled by the constant breeze flowing from the bay and lured by the dancing billows of smoke emanating from steaming hot grills and pans, boisterous crowds of locals and tourists wrestle each other to find tables at the best food stalls. Visitors can enjoy tuna, billfish, flying fish, dolphin (mahi mahi) snapper, lobster, swordfish, kingfish and even conch while they gaze past the fish market and pier to an ocean that is surely full of bountiful riches. They would likely, and understandably, believe that Barbados’s marine area— 426 times larger than its landmass— is the source of their satisfying dinner. Imagine their shock, then, if they learned that 86% percent of the seafood consumed in Barbados, is actually imported.

The drivers of this imbalance, impact food security and nutrition in Barbados. But what causes this vulnerability and what are governments, fisheries and organizations such as the Food and Agriculture

Organization of the United Nations (FAO) doing to reverse these trends?

For hundreds of years, fish have provided Bajans with critical nutrients, vitamins and minerals, while also acting as the healthiest source of animal protein. In Barbados the cultural impact of fish is everywhere: flying fish on the one-dollar coin, dolphin fish in the nation’s coat of arms and a “catch of the day” dish in every rum shop or high end restaurant. Yet, except for flying fish, the ‘catch of the day’ has a high chance of being imported, recently thawed fish.

For hundreds of years, fish have provided Bajans with critical nutrients, vitamins and minerals, while also acting as the healthiest source of animal protein. In Barbados the cultural impact of fish is everywhere: flying fish on the one-dollar coin, dolphin fish in the nation’s coat of arms and a “catch of the day” dish in every rum shop or high end restaurant. Yet, except for flying fish, the ‘catch of the day’ has a high chance of being imported, recently thawed fish.

Given this cultural and social attachment, how can so much of the country’s seafood be imported? Differing tastes between tourists and locals, global markets and overfishing conspire together like trade winds to drive imports and increase Bajan’s reliance upon foreign fish.

While a tourist couple might pamper themselves with a lobster dinner on a romantic Barbados seafront, a Bajan might consider lobster both too expensive and an unpalatable seafloor scavenger. On the other hand, they might prefer saltfish, a key ingredient in Caribbean cuisine dating back to the days of colonial rule and slavery. Back then, as now, saltfish was made from North Atlantic species such as cod and pollock, as well as from smaller species such as herring, and imported as a cheap source of protein. Over time, it became a staple dish. Unfortunately for tourists, lobsters in Barbados are overfished, leading to pricey imports brought in from elsewhere. Regrettably for locals, saltfish is not produced in Barbados, so it must also be imported.

Imports of these two dishes represent the increasing integration of Caribbean economies into the global economy, and the increasing dependency of the region on food imports, particularly for seafood products. The share of imports in total Caribbean seafood consumption increased from 21% in 1991 to 46% in 2016, putting a heavy demand on foreign exchange reserves. The Caribbean region typically imports fish species of lower value (e.g. saltfish and tilapia) while exporting high value species such as lobster and conch.

Imports of these two dishes represent the increasing integration of Caribbean economies into the global economy, and the increasing dependency of the region on food imports, particularly for seafood products. The share of imports in total Caribbean seafood consumption increased from 21% in 1991 to 46% in 2016, putting a heavy demand on foreign exchange reserves. The Caribbean region typically imports fish species of lower value (e.g. saltfish and tilapia) while exporting high value species such as lobster and conch.

Countries such as Bahamas, Belize, Guyana and Jamaica export significant amounts of high-value seafood species such as lobster, conch and shrimp. In Barbados this is not the case as fish imports are generally of higher value than fish exports, mainly due to the limited fish production and high demand by the tourism sector for high value fish (e.g. lobster and salmon) and limited local harvest volumes of high value species (e.g. tuna).

In Barbados, tourists and local fish preferences drive demand for high value seafood. Decreased domestic fish production due to overexploitation, illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishing and the waste and spoilage of fish throughout the value chain at the local level drive the need to import fish. This increased global integration supports international fish trade to ensure fish availability in international markets, but at what overall cost?

According to FAO, the Caribbean Sea is one of the most overfished marine regions in the world with catch trends continuing their decline. This is mainly due to the increasing demands mentioned above, limited fisheries management at the regional and national levels and the low-levels of coordination between Caribbean countries. Fish landings in the region have declined by approximately 40 percent over the last two decades. Some 55 percent of the commercially harvested fisheries stocks in the region are overexploited or depleted and some 40 percent of the stocks are considered fully exploited. Of the fish that is caught, anywhere from 20-30% is derived from IUU fishing which drives further overexploitation. The region-wide loss of coral reefs, with nearly two-thirds of coral reefs in the Caribbean threatened by human activities, also contributes to the decrease in the availability of local fish. Visible impacts of climate change such as large-scale coral bleaching, increasing frequency of high intensity storms and hurricanes, and sargassum influxes will continue to disrupt fishing operations, fish landings and fisher livelihoods. Increases in sea surface temperatures are expected to impact fish production in the Western Central Atlantic, particularly for species that cannot adapt to warmer water.

Fish such as dolphin, tuna, billfish and flying fish do not respect national boundaries, they move from country to country and into areas in the high seas with no national jurisdiction. To sustainably manage these fisheries, all countries must support the same rules and develop joint management plans that consider these highly migratory fish. Unfortunately, the Caribbean is one of the few regions remaining in the world where regional level fisheries management plans for many important fisheries species are not yet in place or implemented (including for tunas, billfish, spiny lobster and queen conch). FAO and its regional partners have developed regional policies and plans for some of these species, but these are non-binding agreements. If countries do not commit to include them in their laws and enforce them, overfishing will not stop.

Fish such as dolphin, tuna, billfish and flying fish do not respect national boundaries, they move from country to country and into areas in the high seas with no national jurisdiction. To sustainably manage these fisheries, all countries must support the same rules and develop joint management plans that consider these highly migratory fish. Unfortunately, the Caribbean is one of the few regions remaining in the world where regional level fisheries management plans for many important fisheries species are not yet in place or implemented (including for tunas, billfish, spiny lobster and queen conch). FAO and its regional partners have developed regional policies and plans for some of these species, but these are non-binding agreements. If countries do not commit to include them in their laws and enforce them, overfishing will not stop.

With respect to the availability of fish to citizens in the Caribbean, high import rates ensure adequate fish supply to satisfy demand. However, high import levels leave the Caribbean vulnerable to any external shocks or market changes, potentially harming food security and lowering food sovereignty. Fish resources are not only a vital source of food, particularly for poorer coastal communities, but they also provide employment and livelihood support for many thousands of people in the region. In the CARICOM countries, at least 64 000 persons are directly employed in small-scale fisheries and aquaculture, while an estimated 180 000 people are involved in fish processing, retail, boat construction, net repair and other related activities.

FAO’s Subregional office for the Caribbean, located in Barbados, works with national governments and national and regional organizations seeking more sustainable and productive fisheries sectors. A potential future where marine capture fisheries are exploited at a sustainable level and where development of a local aquaculture sector increases its contribution to fish supply. FAO’s goal is to improve capacity to manage fisheries at local, national and regional levels while creating economic opportunities in the sector, through a series of projects across the wider Caribbean.

Two specific examples of how FAO led projects intend to strengthen local food security are FAO’s project on Climate Change Adaptation in the Eastern Caribbean Fisheries Sector (CC4FISH) Project and its work to reverse the collapse of billfish fisheries through the Caribbean Billfish Project.

If current trends continue, the impacts of climate change will exacerbate the Caribbean’s reliance on imported fish. To improve resilience, CC4FISH works on improving early warning systems for the fisheries sector, supports the development of a sargassum prediction model to allow countries to better prepare themselves against the influxes of sargassum as well as examine the impacts of sargassum on some of the key fish species (flying fish and dolphin fish), safety-at sea training as well as improving management systems (e.g. through improving policies and legislation). CC4FISH also works with local producers and international partners to transfer successful aquaculture technologies and production systems into the Caribbean as this is still in its infancy in the region. It is providing technical assistance to private sector investments to scale up Caribbean aquaculture production in a sustainable and economically viable way and as a result improve local fish availability. The project also improves food safety and handling of fish, an issue that has plagued the market in Barbados at times as well. In Grenada and Trinidad, a pilot has started to conduct a market assessment for enhanced value added in the fish chain and producing saltfish from local species.

Due to their low price and availability, billfish (marlins, sailfish and swordfish) are a favorite group of fish consumed across the Caribbean, and they are widely eaten in Barbados. Although landed in Barbados as well, estimates are that 60% of the marlins, for example, at the fish markets are actually imported. Recent estimates suggest that stock biomass (that is the amount of fish in the ocean per unit of weight) of blue marlin, white marlin and sailfish in the Atlantic have fallen by 70, 90 and 96%. This is the result of consistent and long term overfishing, particularly by long line fisheries targeting tunas. FAO, through the Caribbean Billfish Project, acts as liaison between Caribbean countries while proposing common measures to sustainably harvest this crucial food source. The project is improving regional capacity to sustainably manage fisheries capturing billfish, tuna and other large migratory stocks. For countries such as Barbados, it is important to commit to working with its neighbors to enforce regional rules and regulations in billfish harvesting fisheries to increase the availability of fish at local markets.

Due to their low price and availability, billfish (marlins, sailfish and swordfish) are a favorite group of fish consumed across the Caribbean, and they are widely eaten in Barbados. Although landed in Barbados as well, estimates are that 60% of the marlins, for example, at the fish markets are actually imported. Recent estimates suggest that stock biomass (that is the amount of fish in the ocean per unit of weight) of blue marlin, white marlin and sailfish in the Atlantic have fallen by 70, 90 and 96%. This is the result of consistent and long term overfishing, particularly by long line fisheries targeting tunas. FAO, through the Caribbean Billfish Project, acts as liaison between Caribbean countries while proposing common measures to sustainably harvest this crucial food source. The project is improving regional capacity to sustainably manage fisheries capturing billfish, tuna and other large migratory stocks. For countries such as Barbados, it is important to commit to working with its neighbors to enforce regional rules and regulations in billfish harvesting fisheries to increase the availability of fish at local markets.

While the fish markets and the Oistin’s fish fry thus create the illusion of copious local fish availability this article has shown that in reality a large majority of these fish are actually imported. Barbados and other Caribbean countries are highly vulnerable to decreases in the sustainability of fish and emerging threats are posing significant challenges to the region. In this regard, the role of International Organizations such as FAO is crucial. FAO exists to work with countries to bring in the best practices from around the globe, improve the availability of fish from the region, build national capacity and encourage regional cooperation to ensure that future generations, including in Barbados, may benefit from their surrounding oceans.

By Iris Monnereau,Roy Bealey, Carlos Fuentevilla

This article has been sponsored by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Subregional Office for the Caribbean. The Authors are Iris Monnereau, Regional Project Coordinator of the Climate Change Adaptation of the Eastern Caribbean Fisheries Sector (CC4FISH) Project, Roy Bealey, Regional Project Coordinator of the Caribbean Billfish Project and Carlos Fuentevilla, Regional Project Coordinator of the Sustainable Management of Bycatch in Latin American and Caribbean bottom trawl fisheries Project.