Sunday Morning. Hurricane season. We are scheduled to head out on a Barbados Blue Dive Boat with a group of scientists but everyone is bringing in their vessels and others are busy recording figures in anticipation of Hurricane Maria, an event that will make landfall in Dominica several hours later with a ferocity that meteorologists describe as something that “has not been seen in modern history”.

Sunday Morning. Hurricane season. We are scheduled to head out on a Barbados Blue Dive Boat with a group of scientists but everyone is bringing in their vessels and others are busy recording figures in anticipation of Hurricane Maria, an event that will make landfall in Dominica several hours later with a ferocity that meteorologists describe as something that “has not been seen in modern history”.

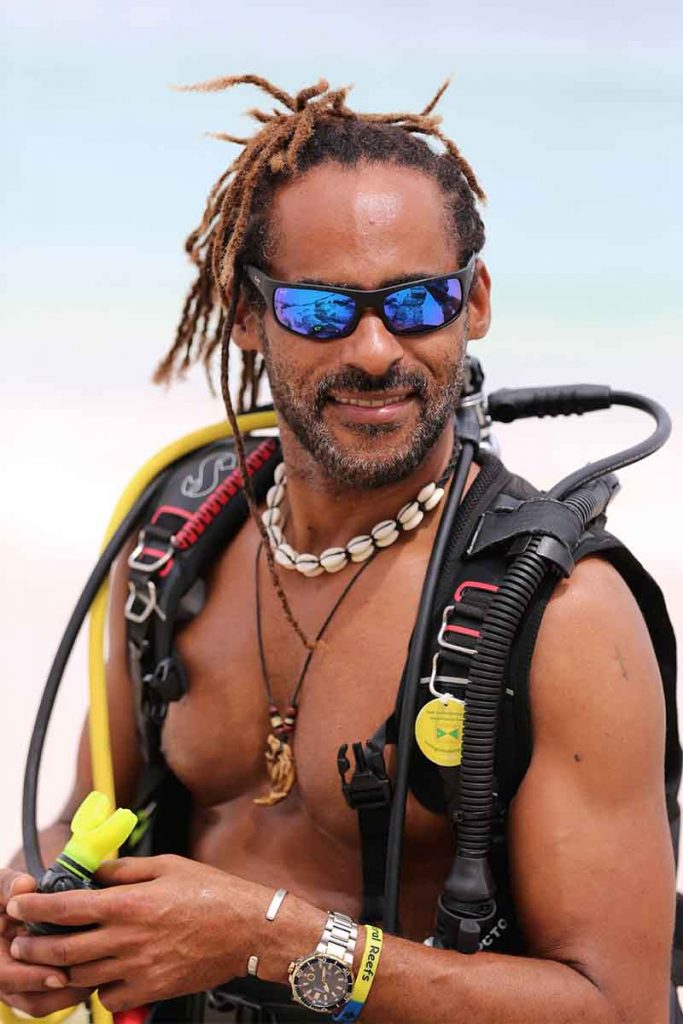

As our shelter stands up to the punishing tides, we try to make light of the impending disaster. nikola simpson, the director of slow fish, nervously giggles as our photographer snaps photos of her wind tussled hair and andre miller, Owner and Operator of dive Barbados Blue, a local Padi dive Operator, momentarily excuses himself to see to his boats.

“Storms like this are bad news for our reefs.” Andre does his best to engage while making a hasty descent. “This is our forest. These are our wildlife,” he asserts, pointing at the raging ocean, now just a few steps away. “We have to protect it.”

The scientists explain how delicate, branching corals are damaged by hurricanes, and how colonies can be overturned. Healthy corals are simply more efficient at regenerating after a natural disaster.

“Robust reefs are tremendously important to the underwater ecosystem. They are essential habitats for fish and reef creatures that produce half of the world’s oxygen,” explains Caroline Bissada, director of east Coast Conservation unit (eCCO) inc., a local environmental consultancy.

Although they cover less than one percent of the ocean floor, coral reefs support more than a quarter of all marine life. Reefs reduce the energetic impact of waves by up to ninety seven per cent, and are necessary for preventing coastal erosion and destruction from storm surges to beaches, coastal communities and infrastructure. Products derived from the reefs are also used in medical research for cures to cancer, arthritis and infections and research has suggested that we are three hundred to four hundred times more likely to find new drugs in the oceans than on land.

Although they cover less than one percent of the ocean floor, coral reefs support more than a quarter of all marine life. Reefs reduce the energetic impact of waves by up to ninety seven per cent, and are necessary for preventing coastal erosion and destruction from storm surges to beaches, coastal communities and infrastructure. Products derived from the reefs are also used in medical research for cures to cancer, arthritis and infections and research has suggested that we are three hundred to four hundred times more likely to find new drugs in the oceans than on land.

Coral reefs are also critical for the economy as they provide millions of jobs to local people through tourism by means of dive and snorkel tourism, fishing, and recreational activities.

since 1970, more than 35,000 surveys conducted at nearly one hundred Caribbean locations show that the region’s corals have declined by more than fifty percent and it is estimated that more than ninety percent will die by 2050.

The cumulative effects of natural disasters, pollution, agricultural runoff and coastal development (leading to poor water quality); climate change impacts (such as coral reef bleaching, sea level rise and ocean acidification) and overfishing, coupled with inadequate government protection, have resulted in mass die offs and disease outbreaks. key reef-building species, such as the elkhorn and staghorn corals, are gravely endangered.

Iris Monnereau, Project Manager at the food and agriculture Organization of the united nations has revealed that the fisheries sector in Caribbean is the most vulnerable to climate change in the world. These findings have been groundbreaking in that they have debunked previous studies that have suggested otherwise.

“With seawater temperatures rising 1-2 degrees above normal temperatures, mass coral bleaching has greatly affected coral reef health,” explains iris. “in 2005 seventy to eighty percent of corals in the lesser antilles suffered bleaching. The following year, research showed that corals had suffered as much as twenty five to fifty two percent mortality, the most severe bleaching event ever recorded for the region. We can see this as a warning of what’s to come.”

“With seawater temperatures rising 1-2 degrees above normal temperatures, mass coral bleaching has greatly affected coral reef health,” explains iris. “in 2005 seventy to eighty percent of corals in the lesser antilles suffered bleaching. The following year, research showed that corals had suffered as much as twenty five to fifty two percent mortality, the most severe bleaching event ever recorded for the region. We can see this as a warning of what’s to come.”

iris, Caroline and nikola are trying to educate fishermen and women about the detrimental effects of overfishing. Caroline has also had some dialogue with farmers and professionals from other industries about chemical run-off from the land and its impact on water quality.

“eighty percent of all marine pollution comes from plastic,” adds Nikola, who is a local advocate for the Plastic Oceans Trust and frequently visits local schools to chat with students on the impact of plastic pollution on the environment.

more than 8 million tons of plastic find its way into the oceans each year— the equivalent of one garbage truck per minute. Instead of decomposing in the environment, some plastic breaks down into tiny pieces called micro-plastics that attract toxic chemicals released over decades from industry and agriculture.

Micro-plastics are digested by corals at a similar rate to their typical food, but when over-consumed they are unable to expel them, which results in a very slow process of starvation.

Micro-plastics are digested by corals at a similar rate to their typical food, but when over-consumed they are unable to expel them, which results in a very slow process of starvation.

Government mandated marine protected areas that restrict human activity for conservation purposes have been helpful in the protection of ecosystems and in sustaining fisheries production. These have been established in Carlisle Bay in st. michael and folkestone in st. james.

Andre was a member of the team that set up the marine park in Carlisle Bay and is the only local dive Operator to offer Padi Coral reef first-aid specialty classes, certifying participants, many as young as fifteen-years-old, to save corals. He has been responsible for saving tens of thousands of corals throughout the region.

Although optimistic about the potential of marine protected areas, Andre is concerned.

“if you do the math, only 1.5 km of the 92 km perimeter of Barbados falls into a marine protected area. Less than one percent of our coastline is protected from over- fishing. more than a quarter of all marine species depend on reefs for existence and of these a large number, such as parrot fish and sea urchins, are keystone species, which means that if they are fished into extinction, it will offset the entire ecosystem,” explains Andre.

Nikola’s work as director of slow fish has focused on reduced and sustainable consumption of these keystone species as well as educating the public. “People need to understand that without reefs there will be no reef fish and without reef fish, there will be no reefs— there will be no fisheries, less coastal protection, less tourism, less recreation.”

Nikola’s work as director of slow fish has focused on reduced and sustainable consumption of these keystone species as well as educating the public. “People need to understand that without reefs there will be no reef fish and without reef fish, there will be no reefs— there will be no fisheries, less coastal protection, less tourism, less recreation.”The scientists unanimously voice a lack of confidence in government enforcement and intervention.

“I’ve seen so many projects that have had to be terminated as a result of limited government funding,” says angelique (angie) Brathwaite, who heads up Blue finance, a united nations environment Program non-governmental organization that develops sustainable financing mechanisms for marine conservation projects.

Angie’s analysis extends beyond the sociological and environmental considerations of her colleagues, advocating for alternative means of support for conservation efforts that do not strictly rely on government funds and bureaucracy.

“We want to get Barbados marine management area [70% of the coral reef habitats] designated as a protected area, not where activities are prohibited but where they can be better managed, but government has taken forever,” says Angie.

“We will fund the demarcation, the signage, the buoys,” continues andre. “Give fish a chance to mate, allow female fish to grow bigger before they are fished, so that they can produce more eggs, and in 3-5 years there will be so many more fish and that will be good for fisheries and the reefs.”

“We’ve killed our sea grass beds and our mangroves. We cannot afford to lose our reefs as well. Barbados is not as bad as some places but then we are also horrible when you compare us to others,” Caroline voices an impassioned plea.

“If we continue to neglect the reefs from a behavioral and a policy perspective, we will witness their destruction within a few decades. This is not just an environmental crisis; this is a full on human crisis.” The future is in our hands.